THE STATE OF HBCUs: TWO CENTURIES OF PERSEVERANCE

For nearly 200 years, HBCUs have been the cornerstone of education, activism, and advocacy for countless Black Americans, yet a continued decline in funding and support is threatening their survival and the question remains: what do we do about it? Perhaps the answer lies at the beginning of the journey.

HONORING THE PAST

Established to meet a need

The first HBCU, The Institute for Colored Youth (originally named the African Institute at its founding and present-day Cheney University of Pennsylvania) was founded prior to the Civil War in 1837 when the pursuit of basic education – let alone higher education – was nearly mythical for blacks in America. Cheyney and the many subsequent HBCUs established prior to the abolition of slavery were founded for the purpose of providing black youth with the training necessary to become teachers or learn an industrial trade.

After the Civil War, black people were still barred from pursuing formal education, and thus, several more HBCUs were founded in the South through the support of the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency established by an act of the United States Congress in 1865 to help former black slaves transition to civilian life. In 1865, Atlanta University (present-day Clark Atlanta University) was founded, and in 1867, Howard University (named after Oliver Howard, one of the founders and head of the Freedmen’s Bureau) and the Augusta Institute (present-day Morehouse College) were both established. In 1868, the Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School (present-day Hampton University) was founded by both black and white leaders of American Mission Association under the leadership of Samuel Chapman Armstrong, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Civil War who supported the abolition of slavery. These institutions and their leaders were pivotal in that they advocated for the expansion of educational offerings to include liberal arts, broadening the scope of professional aspirations for blacks in the post-Civil War era.

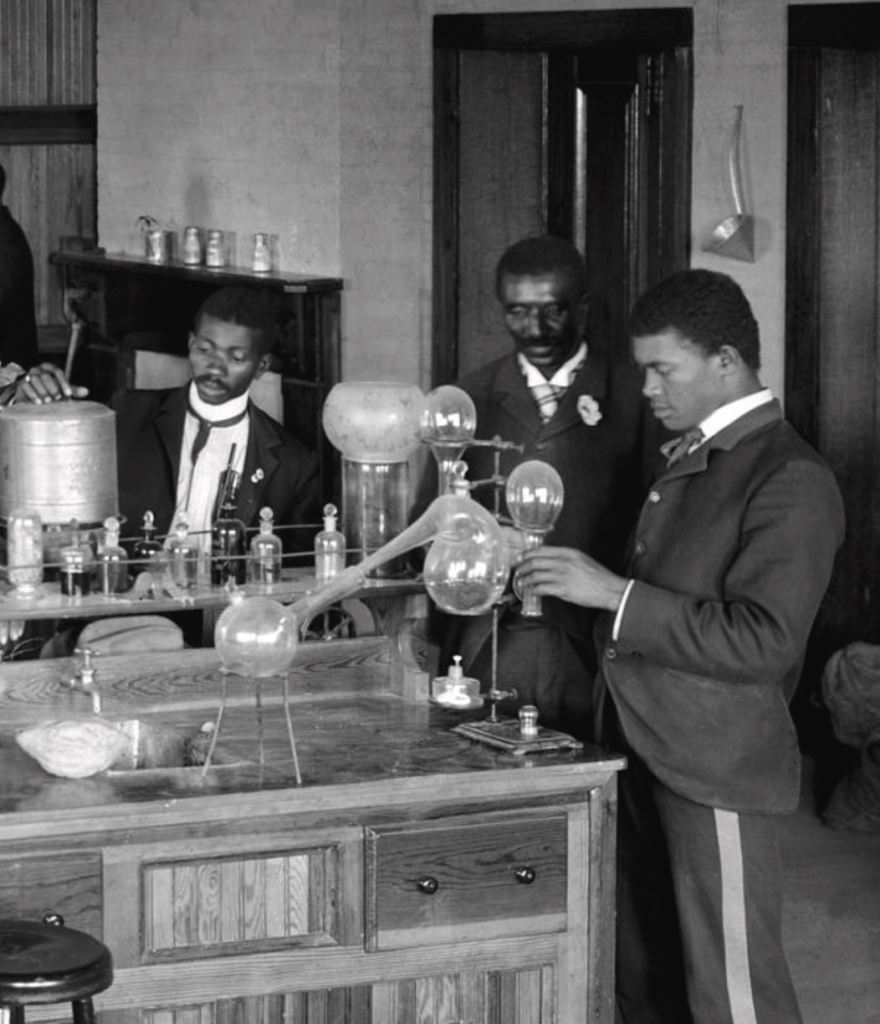

In 1881, Tuskegee Institute (formerly Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers and present-day Tuskegee University) was founded under the leadership of Booker T. Washington, a former slave and graduate of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (present-day Hampton University founded in 1868). In 1896, Washington recruited George Washington Carver to serve as the Head of Agriculture at Tuskegee. Carver served at Tuskegee for 47 years where he revolutionized agricultural science and methodologies.

Thriving in the face of adversity

As the harsh realities of Jim Crow settled upon the freed black person, black people understood that America’s definition of “freedom” only took them so far. Well into the 20th century, aspiring black youth were banned from fully integrating in post-Civil War society, and thus, HBCUs continued to serve as a safe-haven and anchor of liberation and upward mobility for Black Americans.

By the 1950s, America stood at the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement. HBCUs and liberation leaders of the Jim Crow era challenged black students to think of their talents beyond industrial and vocational trade, and the offering of classical academic programs at HBCUs became widespread. Howard University produced some of the most distinguished attorneys of our nation, Meharry Medical College developed prominent doctors, and Bethune-Cookman University produced innovative educators and academic practitioners.

FACT: THE FIRST HBCU, THE INSTITUTE FOR COLORED YOUTH, WAS FOUNDED BY RICHARD HUMPHREYS, A QUAKER PHILANTHROPIST WHO DEDICATED A TENTH OF HIS ESTATE TO ESTABLISH THE SCHOOL.

Leading a movement

The intersection of black oppression and black education fostered a tenacity in black students that changed the course of American History, and HBCUs were at the forefront. In 1954, Howard alum Thurgood Marshall led the victory to Brown v. Board of Education, and in 1960, four freshmen from North Carolina A&T orchestrated the first of many lunch counter sit-ins at the Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C.

The uprising of action against segregation made its way to several HBCUs across state lines including Fisk University, Shaw University and Knoxville College, as each of these institutions were integral to the dismantling of segregation in each of their respective states. Boycotts, protests, and peaceful civil disobedience became commonplace during this era where dorm rooms, campus quads and building basements served as ground zero for movement planning and strategy - and with emerging leaders from HBCUs at the helm.

The historical 1963 March on Washington is considered one of the pinnacle events of the Civil Rights Movement, ultimately leading to the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Of the six leaders (“The Big Six”) who led the planning and organization of the march, four were HBCU graduates: Whitney M. Young Jr. (Kentucky State University), James L. Farmer Jr. (Wiley College), John Lewis (Fisk University), and Martin Luther King Jr. (Morehouse College).

RECONCILING THE PRESENT

End-of-an-Era Shift

While the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provided for the advancement of Black Americans, desegregation helped cast a wider net of schools for black students to attend, and by the 1980s, nearly a dozen HBCUs that once thrived from Jim Crow to the emergence of the black middle class began to decline and were forced to close their doors.

FACT: HBCUs ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR 25% OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN STEM GRADUATES

These closures are the culmination of two major issues: (1) lack of funding by-way-of decreased student enrollment, low alumni support, and discriminate federal programming; and (2) black students matriculating to non-HBCUs at higher rates. As a result, HBCUs became less and less competitive in the national and global education market.

Policy & Advocacy

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter issued Executive Order 12232, which was enacted to establish a Federal initiative designed to combat the decline of HBCUs, and in 1981, President Ronald Regan signed Executive Order 12320, which formally established the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities. The mission of this initiative is to partner with government agencies, private-sector organizations, educational institutions and philanthropic organizations to advocate for the continued competitiveness of HBCUs.

It is important to note that a number of organizations have been at the forefront of advocating for the continued success and impact of HBCUs prior to the passing of these executive orders. Most notably, the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), established in 1944, champions for the mobility and sustainability of all private HBCUs, and the National Association For Equal Opportunity in Higher Education (NAFEO), established in 1969, is an organization that serves the comprehensive interests of all HBCUs with a special emphasis on ensuring that the black voice is heard and applied to the development of higher education policies and programs nationwide.

Subsequent to Executive Order 12232, the Thurgood Marshall College Fund (TMCF) was founded in 1987 and represents the interests of all publicly funded HBCUs. In addition to advocacy at the federal level, TMCF provides a special focus on the leadership development of HBCU students.

FACT: 23 hbcus HAVE closed to date

Adapting to Change

By 2010, HBCUs saw a 50% decline in black student enrollment and with some being faced with losing their accreditation, a number of HBCUs have executed innovative strategies to stay afloat.

In 2017, Paul Quinn College in Dallas, Texas transitioned into a work college, which requires students to participate in a work-learn-service program where each student must work to help offset the cost of tuition.

In 2018, Bennett College lost its accreditation but was able to retain it on appeal in 2019 through the success of #StandWithBennett, a crowdfunding campaign that raised close to $10 million dollars.

With the decline of student enrollment, several other HBCUs have shifted their focus to boosting their international student enrollment. Morgan State University in Baltimore has strengthened its financial stability by enrolling students from abroad who are eager to earn an American education in engineering and other STEM-focused programs.

FACT: HBCUs have suffered a $50 million loss in revenue after the Department of Education amended the PLUS Loan

Private investment

Historically, HBCUs have faced a continuous disadvantage to growing their endowment in comparison to their non-HBCU counterparts. For example, a 2017 Bloomberg analysis found that in 2016 Spelman College had an endowment of $348 million, 21% less than the $1.6 billion dollar endowment of Smith College even though the percentage of alumnae who donate to their respective alma maters are relatively the same.

Notwithstanding, HBCUs have greatly benefited from the generosity of private donors and investors. In 2016, Earvin “Magic” Johnson partnered with South Carolina State University raising $2.5 million to establish an endowed scholarship, and through his organization, SodexoMAGIC, has contracted with seven HBCUs to provide food service operations. Additionally, in 2019 Johnson donated $2 million of unrestricted funds to Grambling University for the advancement of the school’s STEM program.

The recent illumination of the on-going racial disparities in America have motivated substantial philanthropic gifts to HBCUs. In June 2020, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings and his wife Patty Quillin committed to donating $40 million each to Morehouse College, Spelman College, and the United Negro College Fund (UNCF).

In July 2020, MacKenzie Scott made substantial donations to six HBCUs. Scott donated $40 million to Howard University, $30 million to Hampton University, $20 million to Tuskegee University, $20 million to Xavier University (the largest individual gift in the school’s 95-year history), $20 million to Morehouse College, and an undisclosed amount to Spelman College.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

The collective effort

While philanthropic efforts and public advocacy for HBCUs are undoubtedly beneficial, it is simply not enough to ensure the sustainability of the nearly 100 that are currently active, in particular, those that are smaller and less well-known. Private HBCUs such as Howard University, Morehouse College, Spelman College and Hampton University have endowments significantly greater than those of their public counterparts who more heavily rely on federal, state and local funding. However, both public and private HBCUs have seen a sharp decline in federal funding over the past 15 years with private HBCUs experiencing the sharpest decline by 42 percent, and the growth of endowments among both private and public HBCUs trails over 50 percent behind that of non-HBCUs. The combination of endowment disparities and reduced federal funding has positioned all HBCUs at greater risk of hardship.

There is no linear solution to alleviate the threat many HBCUs face but rather requires a collective effort on the part of the federal government, state governments, college and university leaders, alumni, policy makers, and local communities.

FACT: HBCUs HAVE SEEN AN ESTIMATED 27.5% DROP IN ENROLLMENT IN 2020

On the part of the federal government, the White House has increased investment in HBCU programming by 14 percent and Congress reinstated a $255 million investment in STEM programming at HBCUs. However, at the state level many public HBCUs have been gravely impacted by the reduction in funding with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and are experiencing a systemic pattern of inequitable funding.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, HBCUs saw a slight uptick in enrollment; however, that progress has since been jeopardized as many HBCU students are economically marginalized.

On the part of alumni involvement, it is clear that wealth begets wealth, and with the Black-white wealth gap illuminating the fact that white households have wealth that is nearly ten times greater than that of black households, the issue for black alumni is not so much neglecting continued investment into their alma maters but rather having less means to do so.

Perhaps the collective effort reaches into a future that America still aspires to – one where the truth that all men are created equal are not merely words on a page but also makes itself apparent in every facet of our society. Perhaps we reach back into the past, one that reveals so much about the contributions black people have made toward the progress of this nation and to serve as the reminder we all need of why the institutions that developed many of those people should continue to thrive.

Lear more about the White House Initiative on HBCUs.

Learn More about how you can support the legacy of HBCUs.

Additional resources: